Large Transformer Model - Inference Optimization

TL;DR: This note provides a comprehensive overview of LLM inference, including challenges it presents and potential solutions through algorithmic optimization and system implementation improvements.

Estimated reading time: 15 mins

- Overview

- Algorithmic Optimization

- Implementation / System Optimization

- References

Overview

Most contemporary LLMs are based on the transformer architecture. These models process input text sequentially, token by token. The model generates subsequent tokens until a designated termination token, such as <|endoftext|>, is produced, signaling the completion of the output sequence.

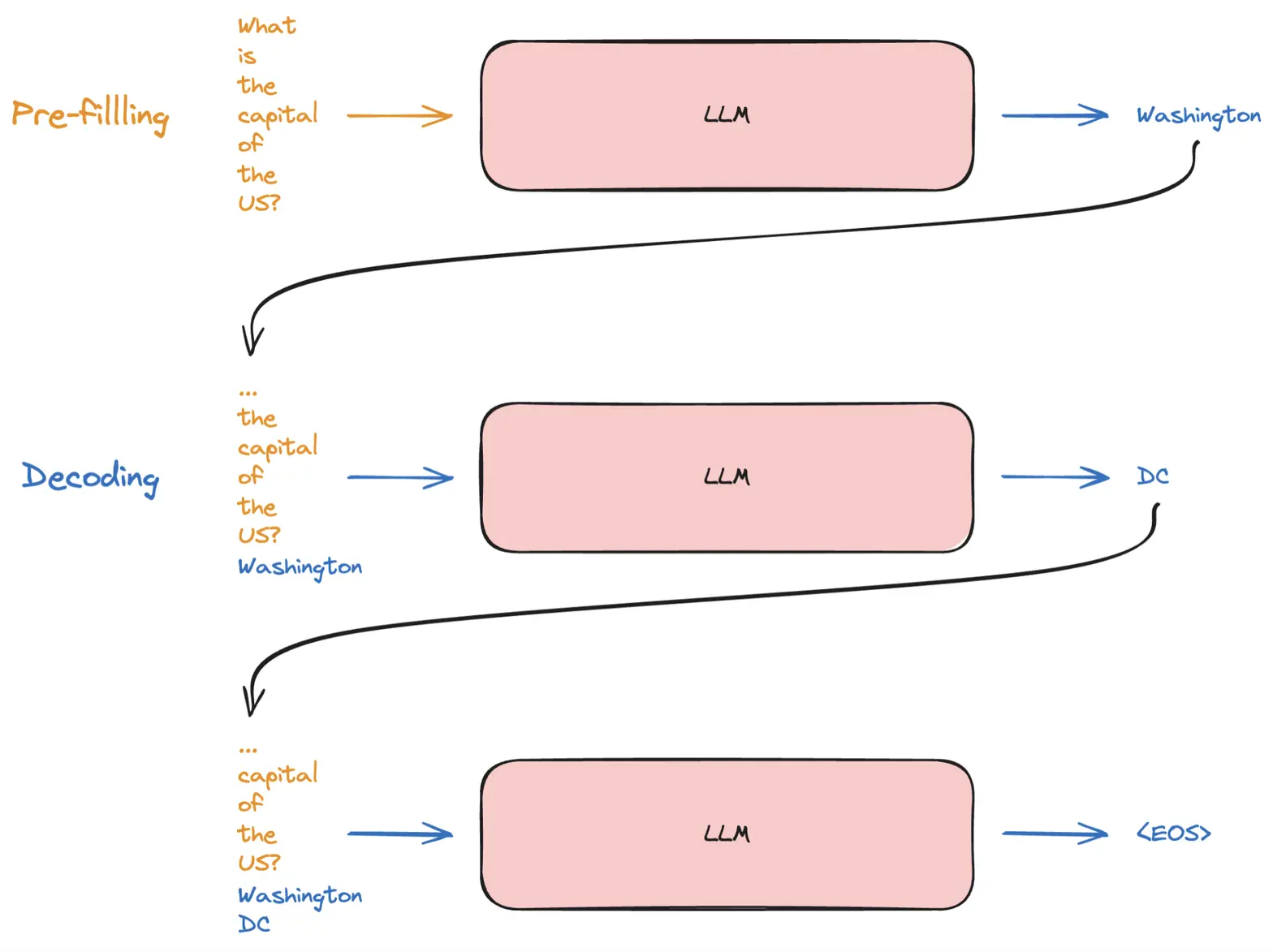

Two-phase Process

LLM inference is generally divided into two phases:

- Prefill Phase (aka initialization phase): This phase involves processing the entire input sequence and constructing key-value (KV) caches for each decoder layer. Given the availability of all input tokens, this phase is amenable to efficient parallelization, particularly for long input contexts.

- Decode Phase (aka generation phase): LLM iteratively generates output tokens, using the previously generated tokens and the KV caches to compute the next token. While the decoding process is sequential, it still involves matrix-vector operations that can be parallelized.

Figure 1: Prefill and Decode phases for LLM inference [source: https://www.adyen.com/knowledge-hub/llm-inference-at-scale-with-tgi]

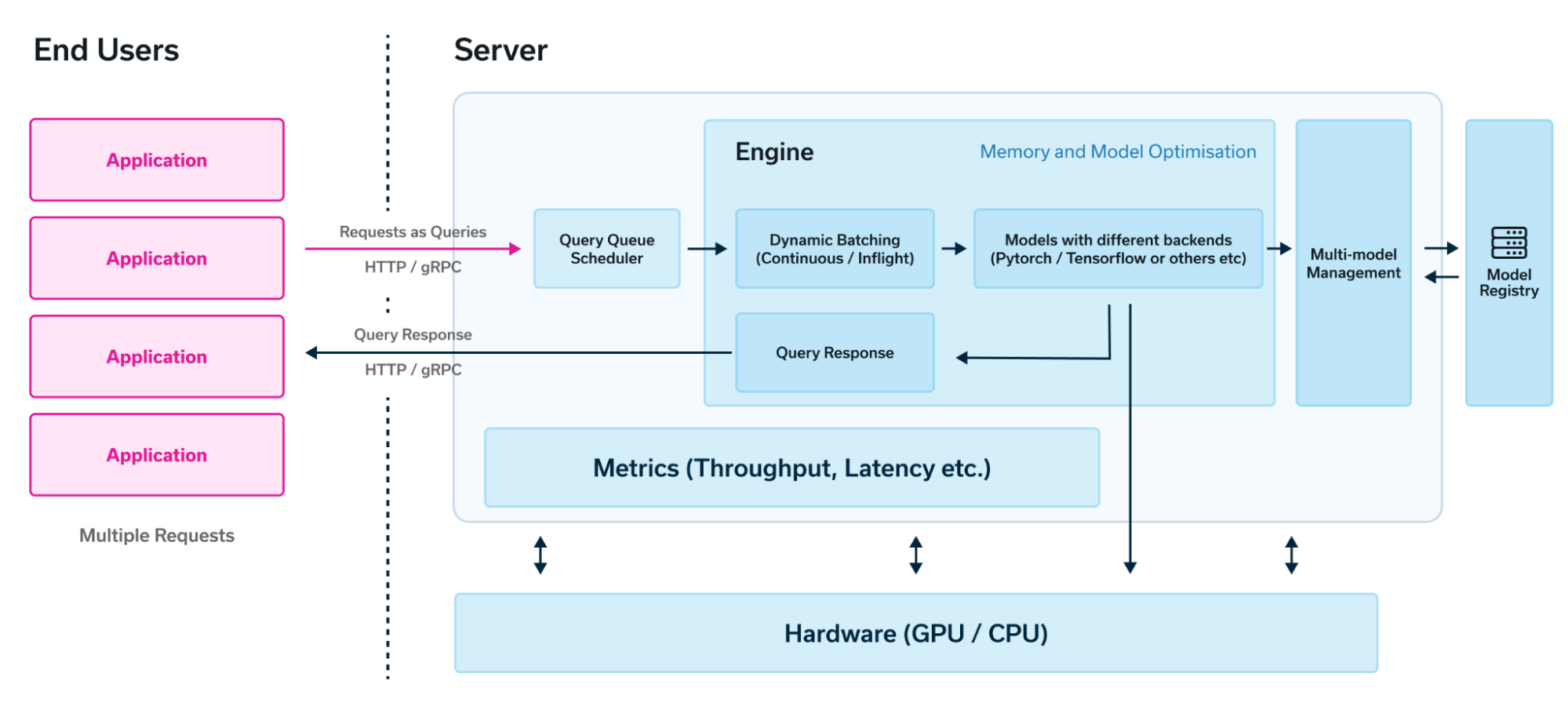

A typical LLM inference server architecture1 is illustrated in the figure below. It includes:

- Query Queue Scheduler: manages incoming queries and optimizes batching for efficient inference.

- Inference Engine: handles dynamic batching and orchestrates the prefill and decode phases. It employs GPUs or other specialized hardware to accelerate computationally intensive operations.

Due to the distinct computational patterns of the prefill and decode phases, they are often optimized separately. This allows for tailored hardware and software optimizations to maximize performance.

Figure 2: Typical Architecture of LLM Inference Servers and Engines

Challenges

There are multiple challenges around LLM inference:

- Heave computation in both prefill and decode phase

- Storage challenge of KV cache: storage requirement

batch_size * n_layers * d_head * n_kv_heads * 2 (K and V) * 2 (sizeof FP16) * seq_len, whered_head = d_model/n_headfor multi-head attention. - Handling super-long context: The capability to handle extensive sequences is essential for applications such as summarizing lengthy documents and RAG. However, this requirement often strains both storage capacity and computational resources.

- Efficient KV cache management when serving multiple queries

The following sections below will discuss different optimizations for LLM inference.

Algorithmic Optimization

This section explores optimizations that modify the LLM algorithm to enhance inference efficiency. We’ll begin with general approaches applicable to many ML architectures and how they are applied to transformer models, including:

- Quantization: Reducing model size and precision by using lower-bit weights and/or activations.

- Distillation: Training a smaller “student” model to mimic the behavior of a larger “teacher” model.

- Pruning: Introducing sparsity by removing unnecessary connections or parameters.

Then, we’ll delve into optimizations tailored to transformer models, discussing several variants designed for more efficient inference.

Quantization

This section explores various quantization techniques, including weight-only or weight+activation quantization. We’ll discuss post-training quantization methods and quantization-aware training. Additionally, we’ll delve into a few SOTA quantization advancements, such as SmoothQuant and activation-aware weight quantization (AWQ).

Weights-only vs Activation Quantization

- Weights-only Quantization (WOQ)

- WOQ focuses on quantizing the model weights. It reduces the model size, leading to faster loading time and lower memory usage during inference.

- WOQ can be a good trade-off between model size and accuracy, especially for large language models (LLMs) where memory bandwidth is a major bottleneck.

- Activation Quantization (AQ)

- AQ quantizes both the weights and activations of the model. It can potentially achieve higher compression ratios compared to WOQ. However, it’s more prone to accuracy degradation due to the presence of outliers in activations2, which can be amplified during quantization.

- Requires careful selection of quantization techniques to minimize accuracy loss. (to be covered later in this section)

In summary, WOQ is generally preferred for LLMs due to its better balance of accuracy and efficiency. AQ can be beneficial for certain tasks if implemented carefully, but requires more fine-tuning to avoid accuracy drops.

Choice of quantization precisions: Typically used precision formats are INT8 or INT4 for weights, while activations remain in FP16 for better accuracy. Recently Nvidia hardware added support for FP8 (Micikevicius et al 2022)3, providing another alternative for quantization.

Post-Training Quantization vs Quantization-Aware Training

- Post-Training Quantization (PTQ) is a straightforward and cost-effective method that directly converts the weights of a pre-trained model to lower precision without requiring any additional training. It reduces the model’s size and improves inference speed.

- Quantization-Aware Training (QAT) introduced by Jacob et al., 20174, allows for training models with lower-precision weights and activations during the forward pass. This reduces memory usage and improves inference speed. However, the backward pass, which calculates gradients for weight updates, still uses full precision to maintain accuracy. While QAT typically leads to higher-quality quantized models compared to post-training quantization (PTQ), it requires a more complex setup. Fortunately, mainstream ML platforms like TensorFlow offer support for both QAT and PTQ (e.g. QAT support in Tensorflow).

SmoothQuant

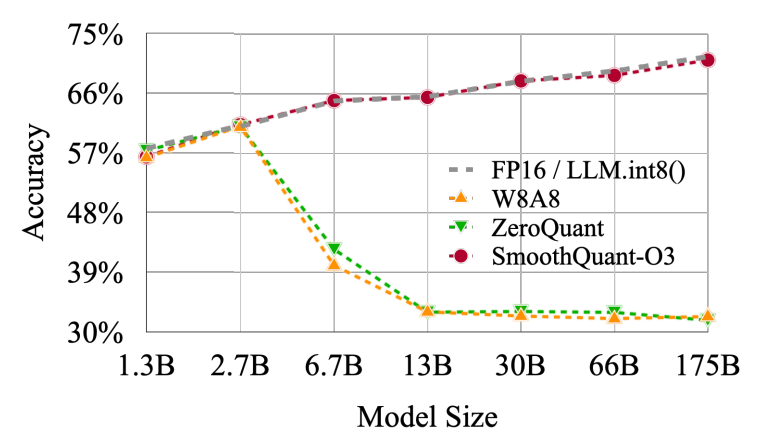

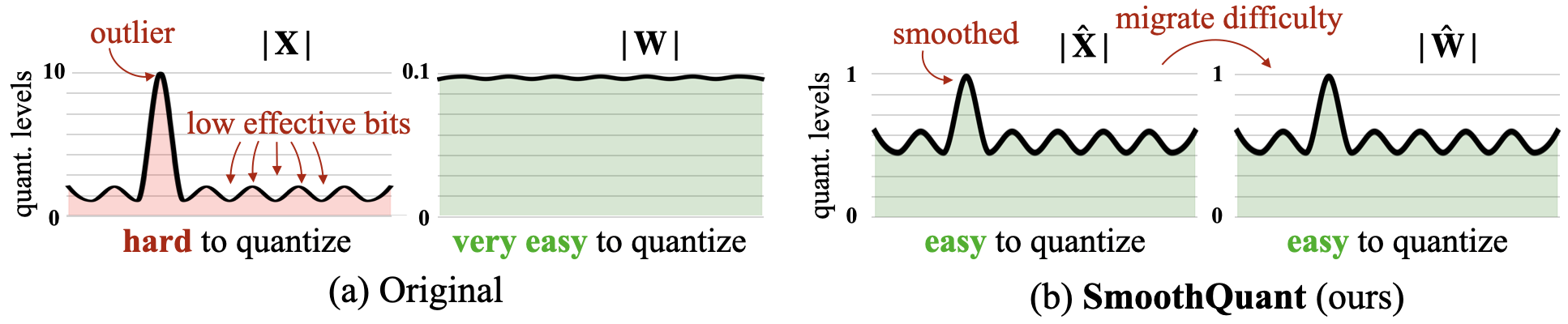

SmoothQuant2 (Xiao et al., 2023) discovered that outliers in activations become more prevalent as the model size grows. These outliers can significantly degrade quantization performance (illustrated in the figure below), leading to higher quantization errors and potentially impacting the quality of the quantized model. In contrast, the weights have fewer outliers and are generally easier to quantize.

Figure 3: Model size vs Accuracy of quantized model [from SmoothQuant paper]

The key idea of SmoothQuant is to migrate part of the quantization challenges from activation to weights, which smooths out the systematic outliers in activation, making both weights and activations easy to quantize. The original paper details how SmoothQuant outperforms other W8A8 quantization approaches in preserving model accuracy.

Figure 4: SmoothQuant Intuition [from SmoothQuant paper]

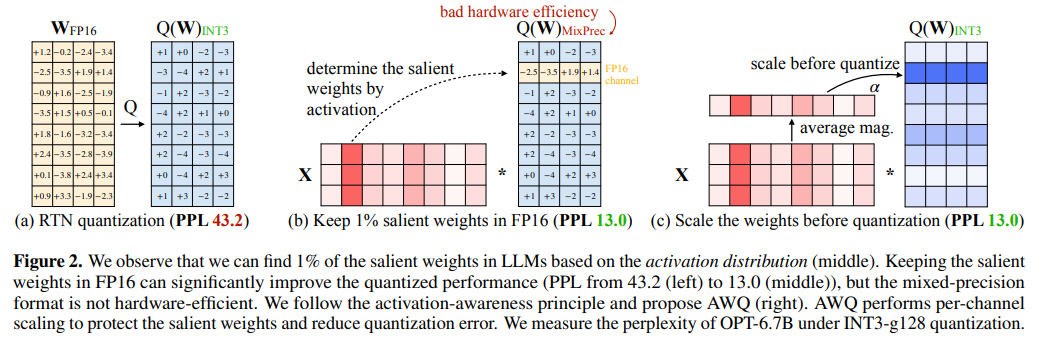

Activation-aware Weight Quantization (AWQ)

AWQ (Lin et al., 2024)5 is a weight quantization technique designed to significantly reduce the size of LLMs for deployment on memory-constrained edge devices. Unlike SmoothQuant, which uses W8A8 quantization, AWQ primarily focuses on weight quantization (W4A16) to achieve substantial size reductions.

The AWQ paper observed that naively quantizing all weights to 3-bit or 4-bit integers can lead to performance degradation due to a small subset (0.1% to 1%) of “salient” weight channels. These channels are critical for maintaining model accuracy. While ideally, these salient channels could be kept at FP16 precision while others are quantized to lower precisions, this mixed-precision approach can complicate system implementation.

AWQ addresses these challenges by:

- Identifying Salient Channels: AWQ leverages activation magnitude statistics to identify salient weight channels that are more sensitive to quantization errors. That’s where the name “activation-aware” comes from.

- Prescaling Weights: To mitigate quantization errors and preserve accuracy, AWQ scales up weights before quantization. This scaling helps to ensure that the quantization process does not introduce excessive distortion.

Figure 5: Salient weights and weights prescaling in AWQ

By combining these techniques, AWQ effectively achieves W4A16 quantization while minimizing performance degradation, making it a promising method for compressing LLMs for deployment on resource-limited devices.

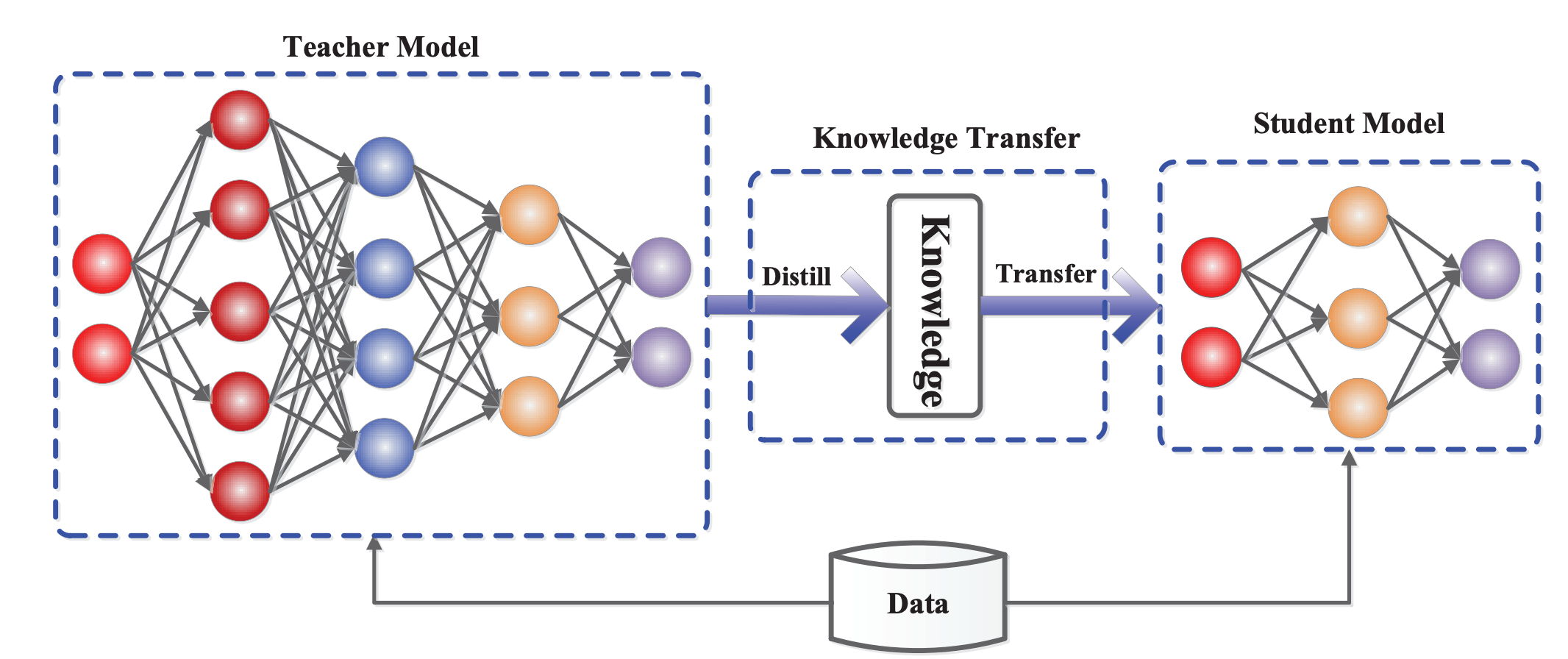

Knowledge Distillation

The high-level idea of knowledge distillation (Hinton et al., 2015) is to transfer knowledge from a cumbersome teacher model to a smaller student model, illustrated in the figure below.

Figure 6: Knowledge Distillation Framework [source: https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.05525]

The key idea of knowledge distillation is well articulated in the following paragraph quoted from the original paper:

- “We found that a better way is to simply use a weighted average of two different objective functions. The first objective function is the cross entropy with the soft targets and this cross-entropy is computed using the same high temperature in the softmax of the distilled model as was used for generating the soft targets from the cumbersome model. The second objective function is the cross entropy with the correct labels. This is computed using exactly the same logits in softmax of the distilled model but at a temperature of 1. We found that the best results were generally obtained by using a considerably lower weight on the second objective function”

It uses a higher temperature to soften the learning objective (the relationship between temperature and actual labels is illustrated in the figure below).

Figure 7: Visualizing the Effects of Temperature Scaling [source: https://medium.com/@harshit158/softmax-temperature-5492e4007f71]

Denoting the logits before the final softmax layer as $z_t$ and $z_s$ for teacher and student models, label as $y$, temperature as $T$, $L$ as cross-entropy loss function, the learning objective described in the original paper can be represented as (formulas can’t correctly rendered in this blog template):

L_KD = L(Softmax(z_t, T), Softmax(z_s, T)) + \lambda * L(Softmax(z_s, 1), y)

Pruning & Sparsity

TODO - add more details

Transformer Model Architecture Optimization

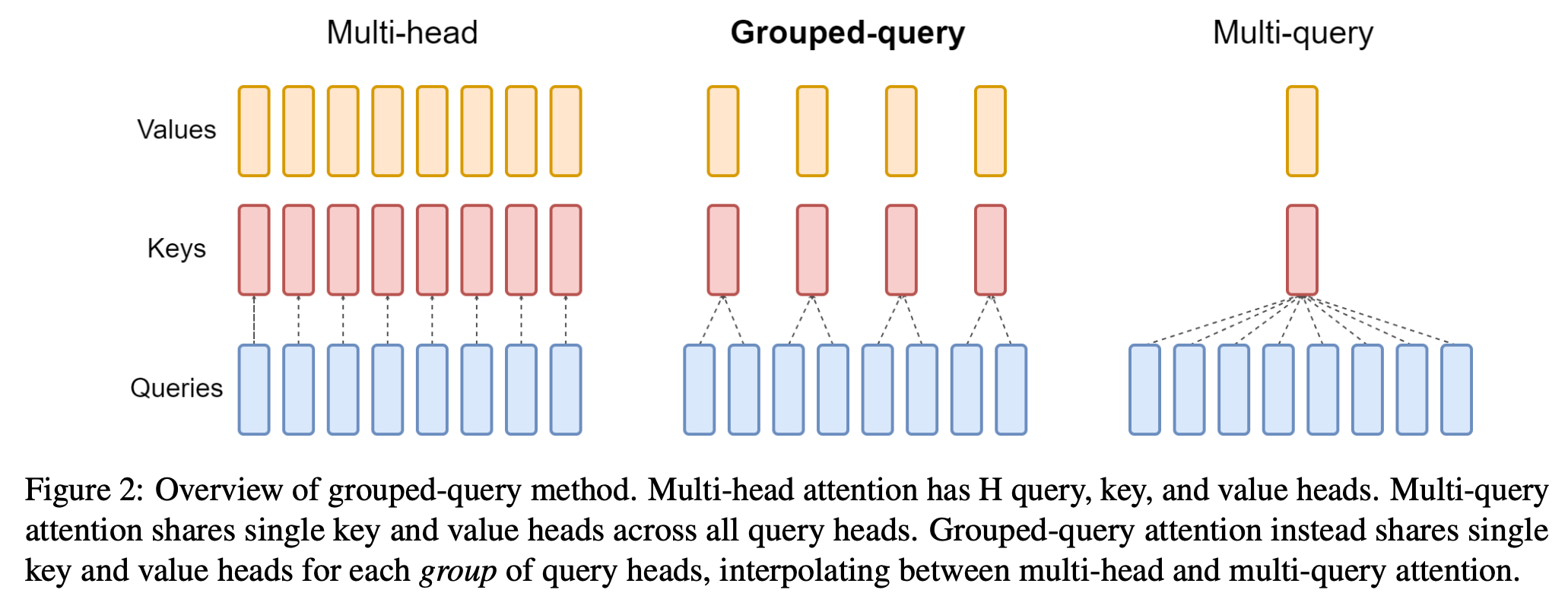

Multi-Query and Grouped-Query Attention

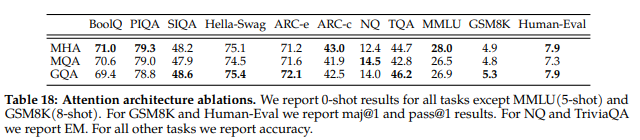

As mentioned previously, the size of the KV cache is proportional to d_model, i.e. n_kv_heads * d_head for multi-head attention. One optimization of reducing KV cache size is multi-query attention (Shazeer et al., 2019)6, i.e. sharing the same key and value among all heads, but still use different queries. This eliminates the n_kv_heads multiplier (becomes 1x) and the KV cache size is proportional to d_head. Different from MQA, Grouped-Query Attention7 (GQA) (Ainslie et al., 2023) shares the same key and value for a group of queries (instead of all).

Figure 8: Multi-Head, Group-Query, and Multi-Query Attentions

Both MQA and GQA are optimizations that trade model representability for smaller KV cache size. While MQA tries to eliminate the n_kv_heads multiplier, GQA is a milder optimization that allows multiple KV heads.

In the study of Llama2 model8 (Touvron et al., 2023), researchers observed that the GQA variant performs comparably to the MHA baseline on most evaluation tasks and is better than the MQA variant on average, details in the table below. And the later Llama-3 model 9 (Dubey et al., 2024) has adopted the GQA architecture.

Figure 9: Accuracy comparison between MHA, MQA and GQA

Mixture of Experts

The key idea of Mixture of Experts (MoE) is to enforce sparsity in model architecture, by allowing the model to scale up the parameter size (i.e. multiple experts) without increasing computational cost. The idea of MoE is not new and can be traced back to Jacobs et al., 199110.

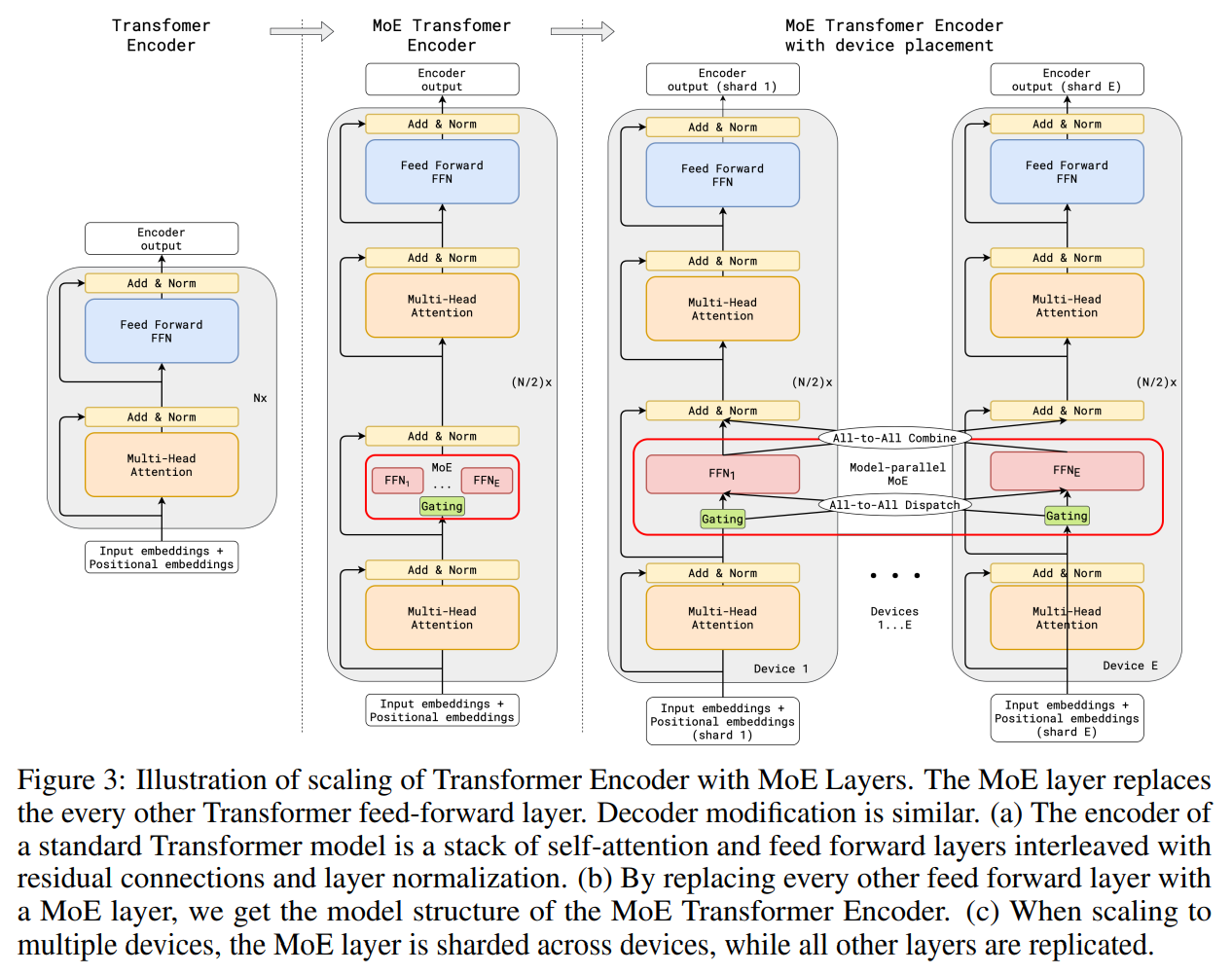

The combination of MoE has been explored by Google in GShard11 (Lepikhin et al., 2020) and SwitchTransformer12 (Fedus et al., 2022), which replace the FFN layers in attention with MoE layers (router + smaller FFNs as illustrated below).

Figure 10: Scaling of Transformer Encoder with MoE layers in GShard

The MoE architecture introduces challenges to model training, fine-tuning, and inference (all experts need to be stored which consumes memory). Particularly, the challenge for training and fine-tuning is the load-balancing of each expert. Some experts might be exposed to a smaller amount of training tokens than others. GShard introduces a 2-experts strategy with the following considerations:

- Random routing: always selects 2 experts, the top-1 and a randomly selected expert based on the softmax probability of the router.

- Expert Capacity: introduces an expert capacity to limit how many tokens can be processed by one expert. When both experts are at capacity, it skips the current layer via a residual connection (some implementation drops the token for training). Another benefit of the capacity is that we can anticipate at most how many tokens will go to each expert ahead of time.

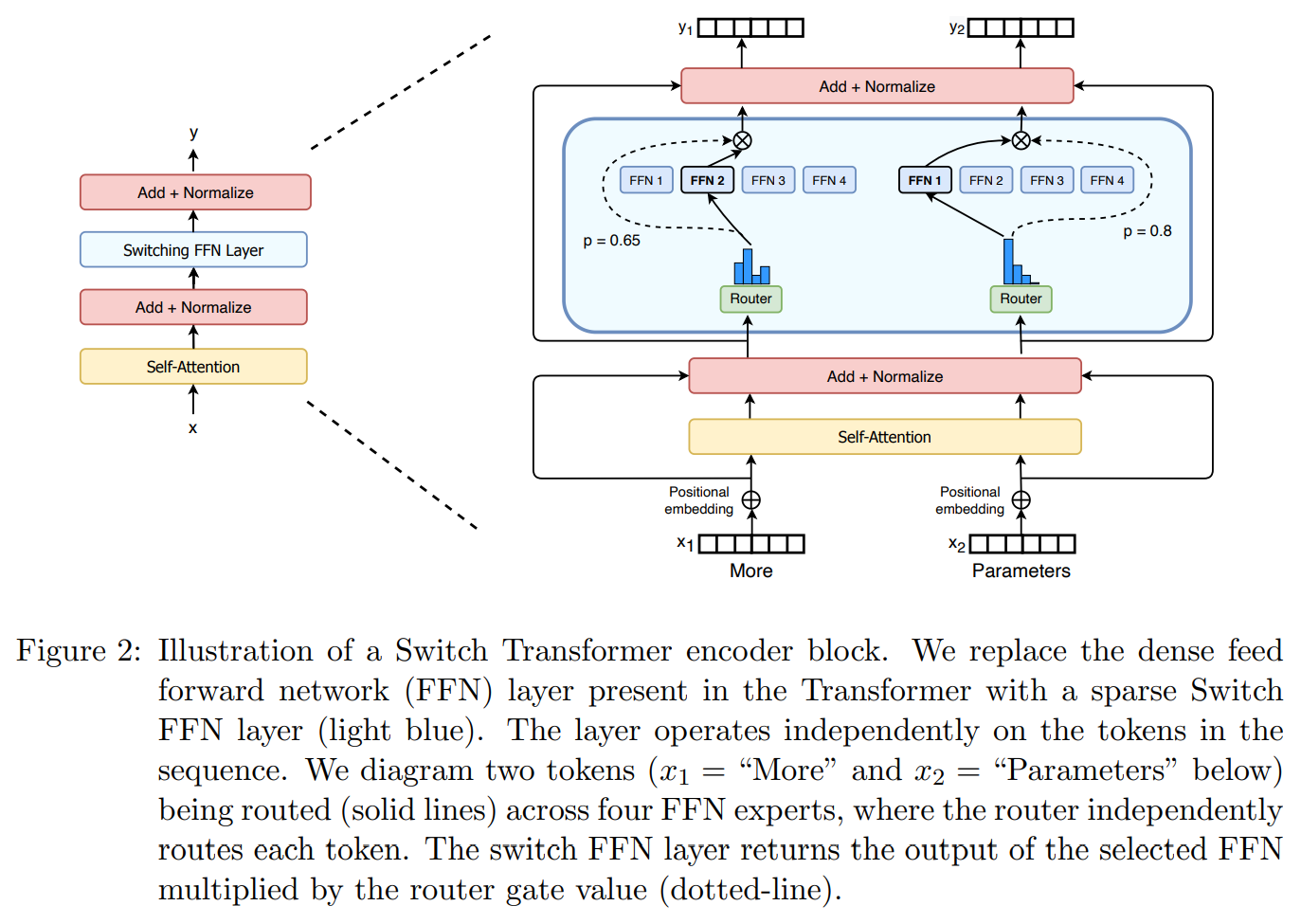

Figure 11: Switch Transformer Architecture

SwitchTransformer simplifies the 2-expert design in GShard to a single-expert strategy and introduces other ideas such as auxiliary loss and selective precision.

- Single-expert strategy: simplified strategy but preserves model quality, reduces routing computation, and performs better.

- Auxiliary loss: added to the switch layer at training time to encourage uniform routing. Similar to other regularizations, it can be weighted using a hyperparameter.

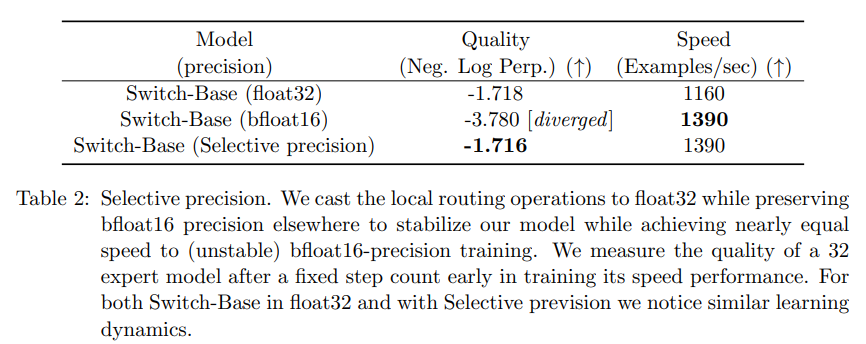

- Selective precision: uses FP32 for routing operations and FP16 elsewhere, which stabilizes the model yet improves the training speed (detail in the table below).

Table: Selective Precision used in Switch Transformer (FP32 for router and FP16 everywhere else)

There are more developments in MoE, which are too much to be included in this note. I will cover them in a dedicated note in the future.

Implementation / System Optimization

vLLM (PagedAttention)

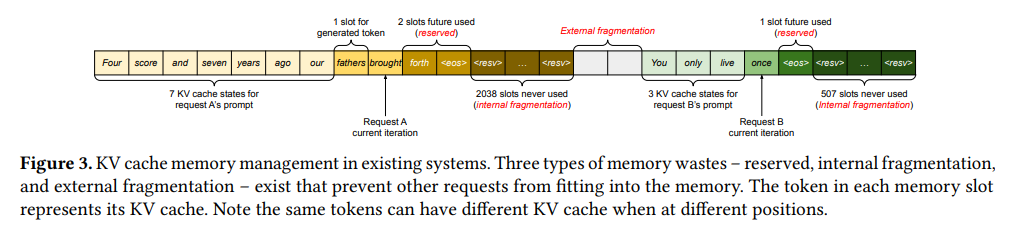

Kwon et al., 2023 13 highlighted the significant memory inefficiency of traditional KV cache management in large language models (LLMs) serving multiple requests simultaneously. The dynamic nature of KV cache sizes, varying based on context and generated token length, often leads to wasted memory due to over-allocation or fragmentation, illustrated as below.

Figure 12: Memory waste in KV cache memory management [source: vLLM paper]

vLLM’s Paged Attention Approach

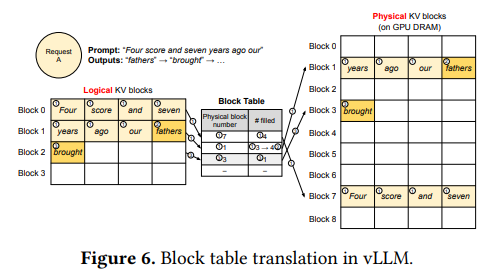

To address this issue, vLLM introduces a novel KV cache management technique inspired by operating system page tables. The KV Cache Manager maintains a logical-to-physical mapping between each request’s KV cache and underlying physical memory blocks. This approach offers several key advantages:

- Efficient Memory Utilization: By allocating physical memory in fixed-size pages, vLLM minimizes fragmentation and reduces memory waste.

- Dynamic Scaling: The system can efficiently handle requests of varying sizes by allocating or deallocating pages as needed, ensuring optimal memory usage.

- Simplified Management: The page table abstraction simplifies KV cache management, making it easier to implement and maintain.

Figure 13: "Block Table" that maps logical KV blocks to physical KV blocks [source: vLLM paper]

In conclusion, vLLM’s paged attention mechanism provides a more efficient and scalable solution for managing KV caches in LLMs, enabling improved performance and resource utilization.

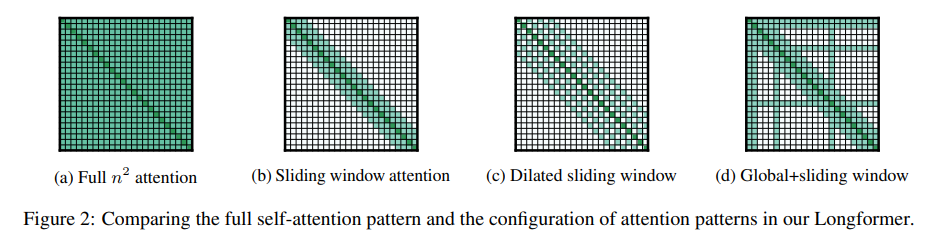

Longformer

Longformer (Beltagy et al., 2020) 14 was designed to handle long documents more efficiently than traditional transformers. The main limitation of standard transformers is their quadratic scaling with sequence length, making them computationally expensive for long inputs.

To address this, Longformer introduces a novel attention mechanism that combines local windowed attention with task-motivated global attention, as illustrated below. This allows the model to focus on relevant parts of the document while still capturing long-range dependencies.

Figure 14: Local windowed attention + task-motivated global attention used by Longformer [source: Longformer paper]

It has shown state-of-the-art results on various long-document tasks, demonstrating its effectiveness in handling long sequences while maintaining high performance.

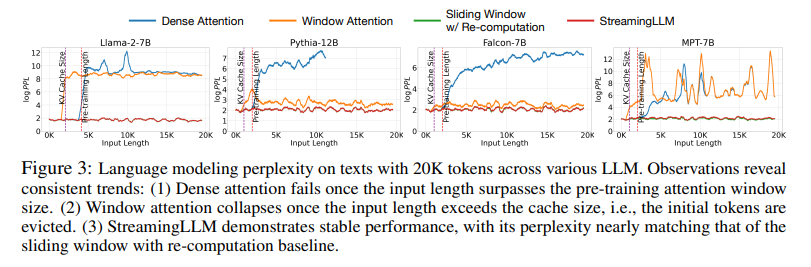

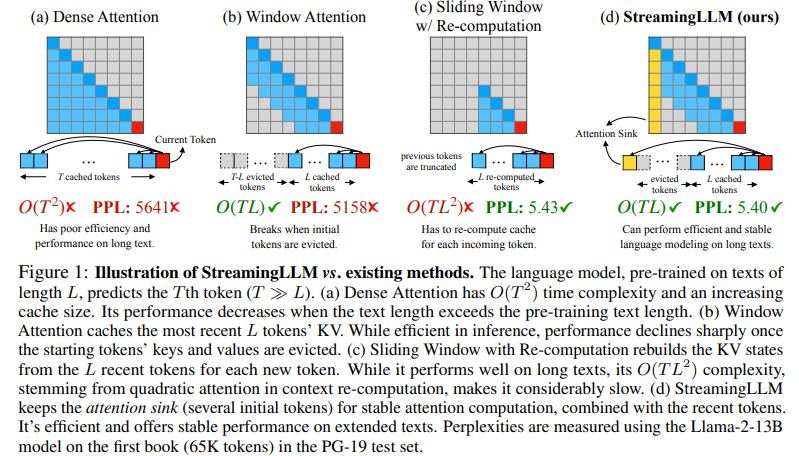

StreamingLLM

(Xiao et al., 2023) 15 brought up additional challenges of decoding with long sequences: 1) excessive memory usage due to KV cache (in addition to long decoding latency), 2) limited length extrapolation abilities of existing models, i.e., their performance degrades when the sequence length goes beyond the attention window size set during pre-training. While Longformer ensures constant memory usage and decoding speed, after the cache is initially filled, the model collapses once the sequence length exceeds the cache size, i.e., even just evicting the KV of the first token, as illustrated in the figure below.

Figure 15: StreamingLLM vs traditional windowed attentions which collapse once input length exceeds the cache size [source: StreamingLLM paper]

Xiao et al., 2023 observed an interesting phenomenon, namely attention sink, that keeping the KV of initial tokens will largely recover the performance of window attention. It also demonstrated that the emergence of attention sink is due to the strong attention scores towards initial tokens as a “sink” even if they are not semantically important.

With these observations, StreamingLLM proposed using a rolling KV cache while always keeping attention sinks, enabling LLMs trained with a finite length attention window to generalize to infinite sequence length without fine-tuning. In addition, we discover that adding a placeholder token as an artificial attention sink during pre-training can further improve streaming deployment.

Figure 16: StreamingLLM vs existing methods [source: StreamingLLM paper]

In streaming settings, StreamingLLM outperforms the sliding window recomputation baseline by up to 22.2× speedup. Interestingly, it also adopted the PagedAttention proposed in the previous section, which allows easy pin-coding of the physical KV block of attention sink tokens in memory.

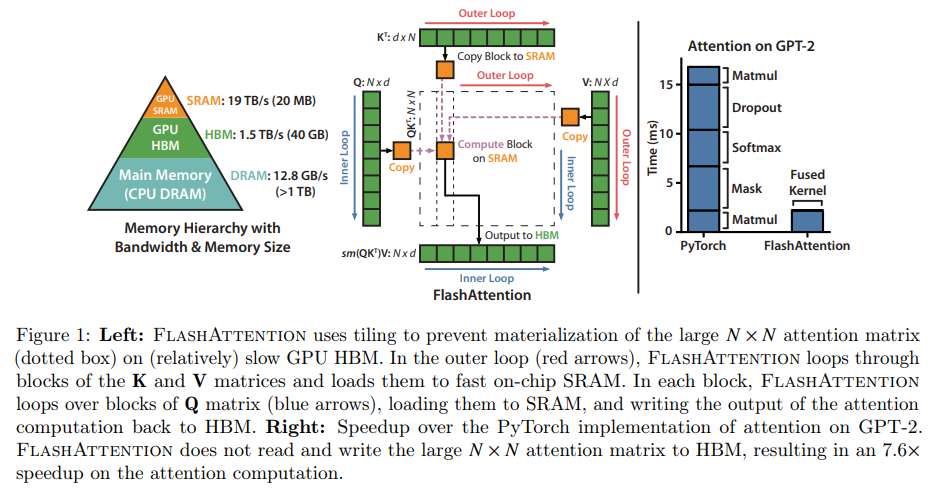

FlashAttention

It was discovered that the majority of time consumed during the context phase is I/O. FlashAttention (Dao et al., 2022) 16 uses the idea of tiling and only loads part of the caches when computing attention scores to ensure more computations are conducted in high-speed SRAM instead of materializing larger NxN attention score matrix on relatively slow GPU HBM and achieve a 4x speedup without impacting model accuracy.

Figure 17: StreamingLLM vs existing methods [source: FlashAttention paper]

FlashAttention is an exact optimization, meaning the computation remains the same as conventional attentions while achieving speedup by optimizing data access patterns (through tiling) and reducing the I/O overhead. You can also find their later work of FlashAttention2 (Dao et al., 2023) 17 and FlashAttention3 (Shah et al., 2024) 18, but I will skip the details here.

Speculative Decoding

Similar to the idea of speculative execution in a pipeline, here it uses a smaller LLM model to predict the next few tokens and applies the larger model to validate the quality of the predictions. Because larger models process a group of tokens instead of one by one, there is more potential to optimize for runtime. On T5-XXL, it achieves a 2X-3X acceleration compared to the standard T5X implementation, with identical outputs.

References

-

Ekin Karabulut, Omer Dayan. “What it means to serve an LLM and which serving technology to choose from”, 2024 ↩

-

Xiao, Guangxuan, et al. “SmoothQuant: Accurate and Efficient Post-Training Quantization for Large Language Models.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2023. ↩ ↩2

-

Micikevicius, Paulius, et al. “Fp8 formats for deep learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.05433 (2022). ↩

-

Jacob, Benoit, et al. “Quantization and training of neural networks for efficient integer-arithmetic-only inference.” Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2018. ↩

-

Lin, Ji, et al. “AWQ: Activation-aware Weight Quantization for On-Device LLM Compression and Acceleration.” Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 6 (2024): 87-100. ↩

-

Shazeer, Noam. “Fast transformer decoding: One write-head is all you need.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.02150 (2019). ↩

-

Ainslie, Joshua, et al. “GQA: Training generalized multi-query transformer models from multi-head checkpoints.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.13245 (2023). ↩

-

Touvron, Hugo, et al. “Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09288 (2023). ↩

-

Dubey, Abhimanyu, et al. “The llama 3 herd of models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21783 (2024). ↩

-

Jacobs, Robert A., et al. “Adaptive mixtures of local experts.” Neural computation 3.1 (1991): 79-87. ↩

-

Lepikhin, Dmitry, et al. “Gshard: Scaling giant models with conditional computation and automatic sharding.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.16668 (2020). ↩

-

Fedus, William, Barret Zoph, and Noam Shazeer. “Switch transformers: Scaling to trillion parameter models with simple and efficient sparsity.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 23.120 (2022): 1-39. ↩

-

Kwon, Woosuk, et al. “Efficient memory management for large language model serving with paged attention.” Proceedings of the 29th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles. 2023. ↩

-

Beltagy, Iz, Matthew E. Peters, and Arman Cohan. “Longformer: The long-document transformer.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.05150 (2020). ↩

-

Xiao, Guangxuan, et al. “Efficient streaming language models with attention sinks.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.17453 (2023). ↩

-

Dao, Tri, et al. “Flashattention: Fast and memory-efficient exact attention with io-awareness.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (2022): 16344-16359. ↩

-

Dao, Tri. “Flashattention-2: Faster attention with better parallelism and work partitioning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.08691 (2023). ↩

-

Shah, Jay, et al. “Flashattention-3: Fast and accurate attention with asynchrony and low-precision.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.08608 (2024). ↩

-

Leviathan, Yaniv, Matan Kalman, and Yossi Matias. “Fast inference from transformers via speculative decoding.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2023. ↩